Book Review: Cracked It! — Problem-Solving and Solution Selling – Reviewed from the Perspective of IT, Agile, and AI

Bernard Garrette, Corey Phelps & Olivier Sibony

Einstein reportedly said that if he were given one hour to solve a problem, he would spend 55 minutes defining it and only five minutes finding the solution. That ratio is the beating heart of Cracked It! — a book that argues, persuasively, that the hardest part of problem-solving is not the solving at all. It is figuring out what the problem actually is.

As someone who has spent years solving problems in IT systems and is now learning to leverage AI, reading Cracked It! gave me fresh insights into how to approach problems and find better solutions for them.

While the book is squarely aimed at strategy consultants, business leaders, and MBA students, its central framework maps surprisingly well onto the challenges IT teams face every day: ambiguous requirements, cognitive biases that derail decision-making, and the perennial struggle of getting stakeholders to actually buy in.

The 4S Method Through an Agile Lens

The backbone of Cracked It! is the 4S method: State, Structure, Solve, Sell. If you have spent any time working in Scrum or Kanban, this sequence should feel familiar.

“State” is essentially problem framing — the equivalent of writing a well-formed user story or defining acceptance criteria before anyone writes a line of code. The authors hammer home a point that Agile coaches have been preaching for years: most failures don’t come from bad solutions; they come from solving the wrong problem. In consulting jargon, they distinguish between “trouble” (the observable symptom) and “diagnosis” (the actual root cause). In IT, we call this “don’t fix the bug report; fix the bug.”

“Structure” corresponds to breaking problems into manageable pieces — think of it as creating an issue tree, much the way you would decompose an epic into stories and tasks. The MECE principle (Mutually Exclusive, Collectively Exhaustive) that the authors advocate is essentially the same discipline behind a clean domain model or a well-partitioned microservice architecture: every component has a clear boundary, and nothing falls through the cracks.

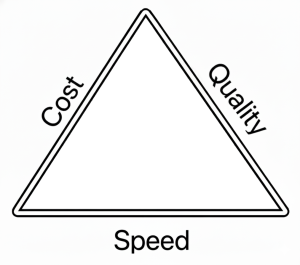

“Solve” is where the book gets genuinely interesting for technologists. Garrette, Phelps, and Sibony present three distinct problem-solving paths and argue that choosing the right one is itself a critical decision:

- Hypothesis-Driven: Fast and efficient, but prone to confirmation bias. This is the equivalent of a senior developer who “knows” what the fix is and jumps straight to coding. It works well when domain expertise is strong but becomes dangerous when the problem is genuinely novel.

- Issue-Driven: Methodical, data-first exploration. This maps closely to how a well-run spike or technical investigation should work in Agile — gather evidence, test assumptions, and converge on findings.

- Design Thinking: Empathy-first, iterative, and user-centred. For anyone building products rather than just systems, this is the path that resonates most directly. It also aligns most naturally with Agile’s emphasis on user feedback and iterative delivery.

The final “S” — Sell — is the one IT professionals most often neglect. The authors dedicate serious attention to the Pyramid Principle and stakeholder communication, essentially arguing that a brilliant solution nobody adopts is a failure. Every engineer who has watched a technically sound recommendation stall and die at the hands of senior leadership will feel this chapter in their bones.

Where AI Changes the Game

The book was published in 2018, before the generative AI explosion reshaped how knowledge workers approach analysis and problem-solving. Reading it now, in 2026, several dimensions stand out.

AI supercharges the “Solve” step but doesn’t replace “State.” Large language models can synthesise research, generate hypotheses, and even draft issue trees in seconds. But the authors’ most important insight — that problem definition is where most people fail — becomes even more critical in an AI-augmented workflow. Feeding a poorly stated problem to an LLM doesn’t produce a good answer; it produces a confidently wrong one. The discipline the book teaches around crafting a precise problem statement is arguably more valuable now than it was pre-AI, because the cost of exploring a flawed hypothesis has dropped so low that teams can waste enormous effort chasing AI-generated red herrings without realising they never properly framed the question.

Confirmation bias gets amplified, not eliminated, by AI. The authors warn extensively about confirmation bias in the hypothesis-driven path. AI tools can make this worse: if you prompt a model with your existing hypothesis, it will happily generate evidence that supports it. The book’s recommendation to actively seek disconfirming evidence is an essential discipline that every team using AI for analysis needs to institutionalise.

Design thinking and AI are natural partners. The book’s design thinking path — with its emphasis on user empathy, prototyping, and iteration — maps well onto how teams are now using AI to rapidly prototype solutions, run synthetic user testing, and iterate on product concepts at speeds that were unimaginable in 2018.

What Works

The book’s greatest strength is its intellectual honesty. Unlike many consulting books that present a single method as a universal hammer, Cracked It! acknowledges that different problems demand different approaches and gives readers genuine tools to decide which path to take. The case studies — from the music industry’s digital transformation to GE’s redesign of MRI machines for children — are well-chosen and illustrate the frameworks without feeling like padding.

The integration of cognitive psychology research, particularly the work of Daniel Kahneman on biases, gives the book a scientific grounding that many competing titles lack. For IT professionals accustomed to evidence-based decision-making, this is a welcome feature.

The Bottom Line

Cracked It! is one of the most rigorous and practical problem-solving books available, and its relevance extends well beyond consulting. For IT professionals, the 4S method provides a structured complement to Agile practices — particularly in the “fuzzy front end” of problem definition and stakeholder alignment, where technical teams often struggle. In an age where AI can generate solutions at scale, the book’s insistence that stating the right problem is the hardest and most important step feels more prescient than ever.

Reference Links

| Term | Source |

|---|---|

| Einstein problem-solving quote | Quote Investigator |

| Cracked It! (official site) | cracked-it-book.com |

| Cracked It! (Amazon) | Amazon |

| Agile Manifesto | agilemanifesto.org |

| Scrum | Scrum.org |

| Kanban | Atlassian |

| User Stories | Atlassian |

| Acceptance Criteria | ProductPlan |

| Epics, Stories & Themes | Atlassian |

| MECE Principle | Wikipedia |

| Domain Model | Wikipedia |

| Microservices | microservices.io |

| Confirmation Bias | Wikipedia |

| Design Thinking | IxDF |

| Spikes (SAFe) | SAFe Framework |

| Iterative Delivery | Agile Alliance |

| Pyramid Principle | Wikipedia |

| Generative AI | Wikipedia |

| Large Language Models | Wikipedia |

| Daniel Kahneman | Wikipedia |

| Cognitive Biases | Wikipedia |