or Technical Debt and the Tech Radar: Staying Ahead of Obsolescence

Ward Cunningham originally coined the term “technical debt” in 1992 to describe the nature of software development—specifically, the need to constantly refactor and improve inefficiencies in your code. Constant improvement. However, the technology itself becomes technical debt over time.

Consider the shift from handmade items to automation. Once automation arrived, the manual process became technical debt. As things become more efficient, older technology that once did its job adequately falls behind to newer machines and methods.

The Mainframe Example

Take servers and mainframes. In the 1940s and ’50s, computers like ENIAC filled entire rooms. ENIAC weighed over 30 tons, occupied 1,800 square feet, and consumed 150 kilowatts of power. It required elaborate cooling systems and teams of engineers to maintain. The project cost approximately $487,000—equivalent to about $7 million today.

Now consider the iPhone I’m writing this article on. According to ZME Science, an iPhone has over 100,000 times the processing power of the Apollo Guidance Computer that landed humans on the moon. Adobe’s research shows that a modern iPhone can perform about 5,000 times more calculations than the CRAY-2 supercomputer from 1985—a machine that weighed 5,500 pounds and cost millions of dollars. My iPhone uses a fraction of the power, fits in my pocket, doesn’t need a maintenance team, and cost me around $500.

Those room-sized mainframes became technical debt. Not because they stopped working, but because something dramatically better came along. So how do you prepare for the technical trends that signal what’s next to become obsolete?

What Is Technology, Really?

Before we can talk about technical debt in depth, we need to define what technology actually is.

Many people think technology means devices, microchips, or other tangible things. But in reality, technology is simply a process or an idea—a better way of doing something.

Here’s a simple example: if it takes you 15 minutes to drive to work every day, but you find a shortcut that cuts 5 to 10 minutes off your commute, that shortcut is a technology. You’ve found a more efficient process. Hardware and software are just the codification of these processes, whether it’s a chip that handles digital signal processing or a more efficient route for walking your dog.

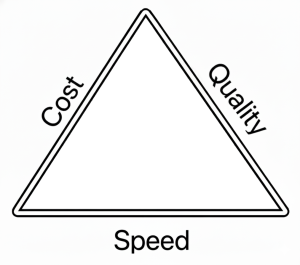

The Triangle of Value

The nature of technology connects to what project managers call the Project Management Triangle (also known as the Iron Triangle or Triple Constraint). This concept, attributed to Dr. Martin Barnes in the 1960s, states: you can have three things, but you can only optimize for two at a time.

Those three things are:

- Cost — How many resources does it take?

- Quality — How good is the output?

- Speed — How fast can you produce it?

Every new technology addresses one or more of these factors. Does it produce better quality? Does it make widgets faster? Does it cost less or require fewer resources?

Once you understand this perspective, technical debt becomes clearer. Technical debt is anything that negatively affects one or more parts of the Triangle of Value compared to available alternatives. Your current solution might still work, but if something else delivers better cost, quality, or speed, you’re carrying debt.

I’m Not an Inventor—So What Do I Do?

It’s true that necessity is the mother of invention. But we don’t know what we don’t know. We don’t always have the right mindset or background to invent a solution to a given problem.

However, others have encountered the same problems and asked the same questions. Some of them are inventors. They do come up with solutions, and they release those solutions into the marketplace.

The question becomes: how do I find these solutions? How do I discover the people who’ve solved the problems I’m facing?

This is where a tech radar becomes invaluable.

What Is a Tech Radar?

A tech radar is a framework for tracking upcoming technical trends that affect your industry. The concept was created by ThoughtWorks, a software consultancy that has published their Technology Radar twice a year since 2010. According to ThoughtWorks’ history, Darren Smith came up with the original radar metaphor, and the framework uses four rings—Adopt, Trial, Assess, and Hold—to categorize technologies by their readiness for use.

But the concept isn’t restricted to IT or computer science—it applies to any field. If you work in manufacturing, aluminum casting, or forging, there are emerging technologies that could make your processes more efficient. If you work in healthcare, education, logistics, or finance, the same principle applies. Some trends, like AI and the internet before it, have broad impact and touch nearly every industry because the common denominator across all fields is the manipulation of data.

The tech radar is a way to systematically track what’s emerging, what’s maturing, and what’s fading—so you can invest your time and resources accordingly.

Building Your Own Tech Radar

There’s a layered approach to building a tech radar, as described in Neal Ford’s article “Build Your Own Technology Radar.” You can enhance this process with AI tools. Here’s how to structure it:

Step 1: Identify Your Information Sources

Start by figuring out the leading sources of information for your industry:

- Trade journals and publications — What do experts in your field read?

- Newsletters — Many thought leaders and organizations publish regular updates

- Websites and blogs — Company engineering blogs, industry news sites

- Professional organizations and memberships — IEEE, ACM, industry-specific groups

- Conferences — Both the presentations and the hallway conversations

- Books — Especially those that synthesize emerging trends

- Podcasts and video channels — Increasingly where practitioners share insights

Step 2: Create a Reading and Research List

Organize your sources into a structured reading list. Here’s a sample format:

| Source Type | Name | Frequency | Focus Area | Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newsletter | Stratechery | Weekly | Tech business strategy | High |

| Journal | MIT Technology Review | Monthly | Emerging tech | High |

| Blog | Company engineering blogs | Ongoing | Implementation patterns | Medium |

| Podcast | Industry-specific show | Weekly | Practitioner insights | Medium |

| Conference | Annual industry conference | Yearly | Broad trends | High |

| Book | Recommended titles | Quarterly | Deep dives | Low |

Adjust the priority based on signal-to-noise ratio. Some sources consistently surface valuable trends; others are hit or miss.

Step 3: Structure Your Radar Spreadsheet

The classic tech radar uses four rings to categorize technologies:

- Hold — Proceed with caution; this technology has issues or is declining

- Assess — Worth exploring to understand how it might affect you

- Trial — Worth pursuing in a low-risk project to build experience

- Adopt — Proven and recommended for broad use

You can also categorize by quadrant, depending on your field. For software, ThoughtWorks uses:

- Techniques

- Platforms

- Tools

- Languages & Frameworks

For other industries, you might use:

- Processes

- Equipment/Hardware

- Software/Digital Tools

- Materials or Methods

Here’s a sample spreadsheet structure:

| Technology | Quadrant | Ring | Date Added | Last Updated | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Language Models | Tools | Adopt | 2023-01 | 2024-06 | Mainstream for text tasks | Multiple |

| Rust programming | Languages | Trial | 2022-03 | 2024-01 | Memory safety benefits | Engineering blogs |

| Quantum computing | Platforms | Assess | 2021-06 | 2024-03 | Still early, watch progress | MIT Tech Review |

| Legacy framework X | Frameworks | Hold | 2020-01 | 2023-12 | Security concerns, declining support | Internal assessment |

Step 4: Use AI to Aggregate and Summarize

If you’re monitoring many sources, you can build an aggregating agent that:

- Pulls in articles from your reading list

- Identifies recurring themes and emerging trends

- Flags when multiple sources mention the same technology

- Summarizes key points so you can triage quickly

Some trends come and go. Others stick around and reshape industries. The goal isn’t to chase every new thing—it’s to assess which trends deserve your attention and investment.

Step 5: Review and Update Regularly

Set a cadence for reviewing your radar:

- Weekly — Scan your newsletters and feeds, note anything interesting

- Monthly — Update your radar spreadsheet, move items between rings if needed

- Quarterly — Step back and look at patterns; what’s accelerating, what’s stalling?

- Annually — Major review; archive obsolete items, reassess your sources

The Cost of Ignoring the Radar

Here’s a cautionary tale. In the 1970s and ’80s, Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) was a giant in the minicomputer market. Co-founded by Ken Olsen and Harlan Anderson in 1957, DEC grew to $14 billion in sales and employed an estimated 130,000 people at its peak.

But as MIT Sloan Management Review notes, DEC failed to adapt successfully when the personal computer eroded its minicomputer market. The company’s struggles helped inspire Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen to develop his now well-known ideas about disruptive innovation.

Olsen was forced to resign in 1992 after the company went into precipitous decline. Compaq bought DEC in 1998 for $9.6 billion, and Hewlett-Packard later acquired Compaq.

The technology DEC built wasn’t bad. It just became technical debt when something better arrived. They were married to their favorite technology and weren’t ready to change with the times.

Conclusion

Technical debt isn’t just about messy code or shortcuts in a software project. It’s about the broader reality that any technology—any process, any tool, any method—can become debt when something more efficient comes along.

The tech radar is your early warning system. Build one. Maintain it. Use it to make informed decisions about where to invest your learning and your resources.

And remember: don’t be married to your favorite technology or methodology. The next wave of technical debt might be the tool or process you’re relying on right now.

References

Concepts and Definitions

- Technical Debt: Wikipedia | Agile Alliance Introduction | Martin Fowler’s bliki

- Project Management Triangle: Wikipedia | Asana Guide

- ThoughtWorks Technology Radar: Official Radar | Birth of the Technology Radar | How It’s Created

- Disruptive Innovation: Wikipedia

Historical References

- ENIAC: Wikipedia | Britannica | Smithsonian | Computer History Museum

- Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC): Wikipedia | MIT Sloan Management Review | Britannica Money | Computer History Museum

People

- Ward Cunningham: Creator of technical debt concept and inventor of the wiki. Wikipedia | Agile Alliance Profile

- Ken Olsen: Co-founder of Digital Equipment Corporation. MIT Sloan Article | Computer History Museum

- Dr. Martin Barnes: Credited with developing the Project Management Triangle concept in the 1960s. Wikipedia Reference

- Clayton Christensen: Harvard Business School professor who developed disruptive innovation theory. Wikipedia

- Neal Ford: ThoughtWorks technologist who wrote about building your own technology radar. Build Your Own Technology Radar

Computing Power Comparisons

- iPhone vs. Apollo Computer: ZME Science | RealClearScience

- iPhone vs. CRAY Supercomputers: Adobe Blog | PhoneArena

Professional Organizations (for Tech Radar Sources)

- IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers): ieee.org

- ACM (Association for Computing Machinery): acm.org

Further Reading

- Book: DEC Is Dead, Long Live DEC: The Lasting Legacy of Digital Equipment Corporation by Edgar H. Schein et al. Amazon

- ThoughtWorks Technology Radar Hits and Misses: ThoughtWorks